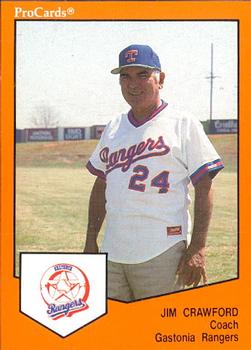

The 1989 Gastonia Rangers coaching staff -- Oscar Acosta, Orlando Gomez and Jim Crawford (courtesy tradingcarddb.com) The 1989 Gastonia Rangers coaching staff -- Oscar Acosta, Orlando Gomez and Jim Crawford (courtesy tradingcarddb.com)

Around this time 10 years ago, I made my first-ever trip to Memphis for baseball. The Triple-A Iowa Cubs were playing a series there against the Memphis Redbirds, so I made my maiden voyage to AutoZone Park – a “must see” on the minor league ballpark circuit.

I went up to the press box to grab a quick pregame meal and game notes, and I showed my official credentials to the press box attendant. She took a look at my ID card and said, “So you’re with the Chicago Cubs, hmmm …” I did the eye roll, since I figured abuse was coming for being a Cubs employee in St. Louis Cardinals country. But then she finished the rest of her statement. “If you really work for the Cubs, tell me who Crawdaddy is.” ***** Crawdaddy’s name is Jim Crawford, but he’s only known as Crawdaddy for the rest of this story. In baseball circles, if I said Jim or Crawford, people wouldn’t know who he was. Heck, about the only thing you might call him other than Crawdaddy is Mr. Crawdaddy. For those of you who don’t know him, Crawdaddy is one of the characters of the game – a longtime baseball scout and a great human being. He retired this year after an amazingly long run as a high school coach, a college coach, a minor league coach and as a scout. Since his own playing days at the University of Southern Mississippi, he spent well over 50 years in the game. But that’s just bio-type talk. That doesn’t tell you who Crawdaddy is. First, let me try and place an image of him in your head. Straw hat on his head … big wad of chewing tobacco in his mouth the size of a baseball. He’ll probably tell you the Hollywood stereotype you’re now imagining would resemble Tom Cruise. Crawdaddy is a lot of things, but stereotype is not one of them. He’s one of the old-time baseball lifers who treated the players he brought into the game like family. “Crawdaddy is a special man. He’s the last of a dying breed,” said Ryan Theriot, who was selected by the Cubs in the third round of the 2001 draft – and was recommended and signed by Crawdaddy. “Analytics, numbers crushers … they’re pushing out guys like Crawdaddy. His value isn’t just X’s and O’s … his value is so much different. People will never understand that until they’ve been in his shoes – and seen what he’s seen. As a player, to be able to appreciate the knowledge he shares about the little things that would have gone unnoticed … that knowledge helps you get there. “I was telling this story the other day, because the SEC Tournament is going on. A catcher for LSU, Jordan Romero, is leading the team in homers. I used to babysit him – which shows you how old I am. He was my neighbor growing up. He’s a junior, so he’ll probably get drafted. He’s been struggling a little bit, and he called me to talk about it. “I said, ‘Jordan, let me tell you what the scout who drafted me told me before the SEC Tournament. He told me that (then-Cubs president) Andy MacPhail – I didn’t know who he was – and (then-Cubs director of player development) Oneri Fleita – who I also didn’t know who he was – were coming to watch me play. That made me nervous. And then Crawdaddy said, ‘Ryan, I don’t care if you make five errors and go 0-for-30. I want you to run on-and-off the field. I want you to run as hard as you can to every base. I want you to run like a deer as fast as you can everywhere you go. They’re not looking at what you do after you get a hit. They’re going to be looking at what you do after you fail.’ That made a lot of sense to me. I never really heard that before. I thought scouts were just looking for the flashy stuff. He explained it to me … ‘What are you going to do when you fail? Because you’re going to fail. It’s going to happen.’ It was a good message, and that was Crawdaddy. Those things go unnoticed. You can’t put a value to that knowledge that he gave me right there. There’s no matrix that you can throw that into and analyze it. That doesn’t exist.” Crawdaddy didn’t actually discover Theriot. It was the other way around – thanks to Ryan’s grandfather, Ray Theriot. “I can remember talking to Crawdaddy in middle school,” Ryan said. “My grandfather actually directed Crawdaddy to our Little League game -- on a field behind the high school field where he was scouting a few guys in Baton Rouge. My grandfather went up to him and said, ‘Hey, you look like a scout. If you want to see a real player, he’s over there on this other field. And Crawdaddy kind of laughed. But that’s how our relationship started – when I was just a young guy, 12 or 13 years old. “Crawdaddy was a presence in my professional life the entire time. Obviously, scouting was what he was there to do. But he was more than that. He was a mentor and a guy that I could ask questions to. I wasn’t the only one. He made the whole process, which is very unnerving, much more comfortable.” Crawdaddy started following him “for real” once Theriot reached the college level. As he did with all the players he was following, it was his job to get to know the player … to figure out his mental makeup … to learn how to push his buttons. As part of that, he learned about the player’s family. He stayed in touch after the draft. He brought a human element to the whole process that people just don’t know about. Take Theriot, for example. As part of the telling of his story, Crawdaddy – without provocation – headed straight to family and keeping up with the infielder during a rough patch. “I liked him as a freshman at LSU,” Crawdaddy said, “and I got to know him really well over the next couple of years. I got to know his grandfather really well. I got to know his mother and daddy. I just liked the way he played. He played hard. He had the ability to play multiple positions on a ball club. He had the speed to play centerfield. He was sure-handed. “I know when he was in the minor leagues, he was sort of struggling. Bobby Dickerson was his manager in Double-A. Theriot said, ‘I’m not getting a chance to play.’ I told him, ‘When you play, make your manager want to play you tomorrow.’ I said, ‘Quit crying, and get to work.’ And he did. Theriot really had a work ethic – and became a pretty good ball player. And he wound up with two championship rings – one with the Cardinals and one with the Giants. He was just a hard-nosed good ball player.” Crawdaddy felt a responsibility to all of the players he signed for professional baseball. It wasn’t just “sign your name here and have a good life.” His words might sound hard nose, but it was his way of saying “I’m there for you if you need me.” “I stayed in touch with all of them,” he said. “My favorite thing … I’d talk to them when they were on the road. I’d call them at 7:00 or 7:30 in the morning and tell them, ‘Get your butt out of bed.’ One of the first things I’d tell them, ‘You ain’t playing hard enough’ – and start a conversation that way. I knew their wives, their family. I would call them to say hello. I would call people in their family to say hello. “I always followed up with them when they were playing. I’d ask them if they had any personal problems they needed to talk about or stuff like that. And ‘How’s Your Mother, How’s Your Father?’ Or with Theriot, ‘How’s your Grandfather?’ “Staying in touch … that’s what you’re supposed to do.” ***** After spending time as the baseball coach at his alma mater – Vigor High School near Mobile, Ala. – Crawdaddy joined the University of South Alabama coaching staff as an assistant coach. In his second year there, athletic director Mel Lucas brought in Eddie Stanky to run the baseball program. Stanky was already a legend when he arrived on campus. He was a three-time All-Star during an 11-year major league career. He was one of the first Brooklyn Dodgers to publicly defend Jackie Robinson. And he came to South Alabama with seven years of major league managerial experience. Crawdaddy figured Stanky had someone in mind to be his assistant coach, so he offered to walk away. Stanky told Crawdaddy that he wanted to give him a year, and then they’d talk about whether a change should take place. They never had that talk. The two spent 18 years together. Crawdaddy couldn’t have asked for a better baseball mind to hang around. “He was way ahead of a lot of people,” Crawdaddy said. “In 1969, we were doing depth perception tests on our players. He wanted to know what a player would be like on Friday night in the SEC against the best pitching. With runners on second base and one out, he’d want to know RBI ratios. With two out and runners in scoring position, what was their percentage of getting them home? Tommy John was one of his favorite players who played for him with the White Sox. He would put up the box scores and he would circle it in red – showing that Tommy had zero walks or one walk. And he was interested in ground balls. His running game was better than anybody’s in the big leagues today. “Stanky was a great person. He was hard-nosed. If he was playing against his mother – if he had to take her out at second base on a double play – he would. He was by far ahead of a lot of people in baseball today. He was far advanced for his time.” Thanks to Stanky and some of the people in Stanky’s circle – like Pee Wee Reese, George Kissell and Harry Walker – Crawdaddy learned some of the most important traits of the scouting world. “I learned a lot just sitting and listening what these guys talked about,” he said. “Coach Stanky taught me two important things to look for that I took into scouting: Work ethic and mental makeup. I would explain to a kid after they signed … You were a big fish in the pond when you were at LSU or Podunk High School. But now, you were just another fish in the pond when you got into pro ball. And you had to work – and work extra hard – to be there.” ***** Work ethic and mental makeup go directly to what makes Crawdaddy special. As a scout, it was his job to know everything there was to know about the athlete. And to get to know the player meant … well … get to know the player. “One of the first things I’d do with all the players – and their mothers would have a fit – I’d want to go see their bedroom,” he said. “Most of that was done in the winter. You get a lot of information that way. You visit them in their home. When I was talking about going into their bedroom, my concern was looking at pictures they had on their wall. Did they have football players or baseball players? It gave me an idea of what his personal makeup habits were. Did he make his bed for his momma? Did he just toss stuff on the floor? “I would take the families out to eat. It became very personal with the players you signed. You wanted them to do well. You wanted them to be a person that anybody with the Cubs would want to have as a friend.” As a scout, you can do a lot of legwork and just not see the rewards. For instance, you can project a player to be selected in the fourth round. If the team two slots before you picks that player, the scout was correct – but didn’t get his guy. “You’ve only got a one-in-30 chance of drafting a player with the way the draft is,” Crawdaddy said. “You had most of them right in the draft. You just didn’t get them because of where your team picked in the draft. So it’s all about just knowing the people in your area. “All of it was fun. I had a great time.” ***** When the press box attendant in Memphis jokingly asked me to tell her who Crawdaddy was, I laughed. Crawdaddy had warned me about her a few days before, telling me to give him a call if she gave me any grief. He then ended the conversation with his patented “This is Crawdaddy, over and out.” His career was full of listening, learning and observing – and giving correct scouting reports. Crawdaddy may be retired now, and he may not travel as much as he used to, but – as he’s told me many times – he’s still above ground. I’m going to make sure checking on him is part of my regular routine. As Theriot neatly summed it up, “It’s been a long life on the road for that little man. That dude’s had some miles under his feet, for sure.”

12 Comments

I had an awesome back-to-back stretch on the phone Thursday morning.

First, I had a nice long conversation with Jim Crawford – only known in baseball circles as Crawdaddy. Crawdaddy had a long and storied career in the game – working side-by-side with the legendary Eddie Stanky for 18 years. Crawdaddy then went on to scout for the Cubs for over 20 years – and one of the players he signed was Ryan Theriot. I’ll be writing at length about Crawdaddy for my next story, including how the scout was first introduced to the young ballplayer. As for The Riot, for those of you who are regular readers, you know I’ve been on a mission to track down players I worked with to talk about their playing days and find out what they’re up to now. I interviewed Ryan for the piece on the scout who signed him, and then we talked about … well … Ryan Theriot. Chuck: So, what are you up to now? You’re all over social media with your sports performance facility. What’s going on there in Baton Rouge? Ryan Theriot: “It’s called Traction Sports. We train major league baseball players, minor league players, NBA, NFL, you name it. We have nine golfers on the PGA tour that train here and a few tennis players. It’s a huge sports performance facility – 29,000 square feet – and we have physical therapy attached. We have a youth baseball program … 7-on-7 football program … lacrosse program for the amateur players. It’s a true multi-sport facility. I bought part of this after I retired. It’s where I trained when I was playing. It’s been growing tremendously ever since. At the last NFL draft, 17 guys that are on an NFL roster right now trained here in preparation for the draft. I don’t know that there’s another facility in the country that has that many first-year guys. It’s a really thriving business and a lot of fun.” Chuck: Are you involved in it 24/7? Theriot: “Yes I am. I’m involved. I’m basically the general manager. I assist in all facets of the business. Baseball is my wheelhouse, but I’m not the baseball director. I don’t know if you remember Brad Cresse – he was a catcher here at LSU and played for the Diamondbacks organization for a few years – but Brad is our director of baseball. Chad Durbin, who was a longtime major leaguer, handles pitching. Ryan Clark, former NFL safety and ESPN analyst, is an owner as well and heads up the football division. So there’s a lot of expertise here. Pete Jenkins, who is a Hall of Fame NFL defensive line coach, is our defensive line instructor. Kevin Mawae, who is getting ready to be in the Hall of Fame, does offensive line. From a skills standpoint, I don’t know if there’s a place in America that has this many professionals that are here every day that are teaching. It’s a really unique situation. We’ve been blessed that there are as many guys with this much knowledge that are actually willing to be here and work. It’s pretty cool.” Chuck: And you pretty much went straight there directly after winning a World Series in 2012. Theriot: “When I was playing, toward the end of my career, I had some talks with the owner here about getting involved and some of the ideas I had to possibly help this place grow. It was an easy transition for me and it was something I knew that I was going to do. I just jumped into it, and the rest is history.” Chuck: I think it’s great … You went out on your own terms and walked into a great situation. It made for a perfect transition. Theriot: “It was. I knew it was time. My kids were getting a little bit older. I achieved everything in the game that I could have ever imagined that I would achieve, plus some. I was fortunate to play for some storied organizations. Obviously, Chicago – the club that drafted me and the club I spent the most time with. Then from Chicago to Los Angeles … who doesn’t want to play for the Dodgers? Then to St. Louis, where I played for maybe the greatest manager of all-time in Tony LaRussa. I was able to play there for a year and learn from him and win a World Series ring. And then … San Francisco. Bruce Bochy is going to be in the Hall of Fame as well, and I won a ring there. I couldn’t have asked for a better run there at the end. The stars just aligned and put me in a good spot. I got to play for Joe Torre … LaRussa … Bochy … Lou Piniella … Dusty Baker. Guys who were just great baseball men – and good people, to boot. You learned a lot from them.” Chuck: With that kind of knowledge, do you want to eventually go into coaching? Theriot: “I’ve had offers, and I’ve entertained the thought. Let me just say this … I would love to at some point, but right now is not that time for me. But I will. Right now, I’m coaching my son’s 10-year-old baseball team – and loving it. And dammit, these kids can play … (Laughing) … I tell them, ‘We’re not going to be the biggest, the strongest or the fastest – we’ll be a little bit like Coach Ryan – but we’re going to play hard.’ And that’s what they do. Coaching is something I see in my future at some point. Right now is not that time. But I’ll be out there some time coaching, I’m sure.” Chuck: I figured out that your son is 10. How old are your daughters now? Theriot: “9 and 7.” Chuck: I remember so many times leaving the ballpark and seeing you and your wife pushing a stroller across the street from Wrigley Field – either by McDonald’s or down Addison Street by Taco Bell. Theriot: “(Laughing) Yeah, we popped another one out every year. Johnnah was able to do some amazing things with those kids. You know, it’s not talked about enough … the wives, the families, what they go through and what they sacrifice for the players to have success. That stability and support system at home are super important. It’s really evident in a lot of guys who have that super support system – because they can play the game for a long time. They have success and they’re great teammates. Johnnah did a lot and was able to keep everything together. I’m trying to repay her as much as I can now. I bring the kids to school every day. I’m Mr. Mom.” Chuck: What were your fondest memories of playing at Wrigley Field? Theriot: “Midweek day games used to blow me away. I was amazed that so many people showed up for a Tuesday 1:20 game. The place was packed. The fan base in Chicago is unlike anywhere else. Talk about passion. They appreciated the small things of the game. You know, the things that I did well. I wasn’t going to hit a bunch of homers. But I played hard and gave 100 percent all the time. And truthfully, I got the most out of my ability – and they appreciated it. That fan base … the knowledge of the game in Chicago is different than anywhere else. The fans really get it. They understand the small things that make teams win. And I feel like they really appreciated it. So my fondest memory really would be the fans. It would be the fact that they were there every day and they understood the game.” Chuck: And the broadcasters, too, dubbing you “The Riot.” Theriot: “Ron Santo, first and foremost, was one of those guys … shoot, the stuff that man did for the Chicago Cubs organization. Broadcasters, top to bottom, it was amazing. It was an unbelievable time in my life. I was truly blessed and fortunate to spend as many years as I did with the Cubs organization.” Chuck: You had a nice run with the team, including a couple trips to the postseason. Theriot: “2007 and 2008 in Chicago were unbelievable. Those two seasons were magical. Obviously, they didn’t end up the way you wanted them to end up – but that’s how the playoffs go. We had to travel to the West Coast, which is never easy to do – those cross-country trips. I think if we didn’t travel as far, there would have been different outcomes. But there were close to 200 wins those two seasons. Those two years were awesome.” Chuck: And then you topped it off winning World Series rings in 2011 and 2012. Theriot: “I should have said this before. It was good that I left when I did – because I still had a love for the game. I’ll sit at home in the evenings before I go to bed all the time and watch the MLB Network for an hour just to catch up and see how everyone’s done that day. I’ve heard stories from guys about – when they were finished – they didn’t want anything to do with the game. And I couldn’t be any farther from that. It was perfect timing for me.”

I’m not going to lie … The stories I get the most feedback on – and the most page hits – are the stories about former Cubs players.

And I should get solid feedback on them. They’re recognizable names. They’re good people. They’re fun to write about. But sometimes, what gets lost in the shuffle, are the people who were right there with these guys prior to the beginning of their professional careers. Baseball scouts are the lifeblood of the sport. These are the people who truly do their jobs because of their love of the game – although hotel points are a nice perk. It’s the ultimate no-frills job, in that it’s hard to quantify what “successful” is. You work long hours … in different towns every night … and you’re seemingly always away from home. It’s a nomadic existence, yet it’s one the game depends on. For anyone who wants to argue scouts vs. stats, there’s more to it than passing the eye test. When you’re an amateur scout, you’re out looking at high school kids and college kids virtually year-round, trying to “discover” somebody and finding out everything there is to know about the kid. That includes uncovering the warts, and getting to know the parents, and trying to find red flags. You can sit on a kid you love seemingly forever; at the last moment, another club swoops in and drafts that kid before your organization had the chance to. Such is the life of a scout – lots of risk, and oftentimes no reward. And when I say “discovered,” it’s hard to say Kerry Wood was “discovered” when Woody was the fourth overall selection in the draft – but a scout had to stick his neck on the line and make his case for a 17-year-old high school pitcher. Bill Capps had to do his homework and did just that. For every first-rounder like Wood who has a long career, there are players taken lower in the draft that indeed were “discovered” by scouts living the wandering life. I was fortunate to be able to meet and listen to some of the great scouts in the game. My best “shut your mouth and open your ears” lessons came from listening to the people who truly did their jobs for the love of the game of baseball. My introduction to scouts first came in my early Cubs days, when I had the awesome opportunity to just listen to some of the great storytellers who have long since passed away – scouts like Hugh “Uncle Hughie” Alexander and Gene Handley. I need to make it my mission to incorporate scout tales into my story rotation. For those of you who read my writing just because you can (Thank You!), I’m looking forward to introducing some of these baseball storytellers to you. For those of you who are former players and/or scouts, I look forward to sharing stories of your baseball brethren (Hint, Hint – I can be bribed to write about you! I like hotel points, too). A quick “missed opportunity” for now, with plans for scout stories later in the summer after the draft. ***** I wish I had a tape recorder the first time I met Spider Jorgensen. Actually, I wish I knew the Spider Jorgensen story before I met him. I would have come armed with questions. During one of my first seasons with the Cubs, there was a two-day retreat to some resort in the far western suburbs. It was one of those bonding experiences that HR people like for company morale. I’ve bit my tongue on the logic of in-season retreats for nearly 30 years, but that’s another story. Anyway, a few scouts were basically ordered to be there. It was their “reward” for surviving another draft; they got to spend another couple days away from home – this time hanging out with mostly business-side people they didn’t know. Again, it was all in the name of bonding. I worked at Wrigley Field with everyone at my table except for an older gentleman – and none of us had met him before. We all introduced ourselves, and he told us he was John “Spider” Jorgensen from Rancho Cucamonga, California – and he was an area scout. As a group, we asked him questions about the work he did, and he was very modest. He barely admitted that he had ever picked up a bat or glove. We never got much out of him about his life, other than he was a longtime scout and he loved what he was doing. He was just happy to find players who fell below the radar, and one of his guys was Mark Grace – a 24th round pick in 1985. The next morning at breakfast, Gene Handley – a scout for, I’m guessing, 50 years – was telling stories from his baseball career. He had literally spent his entire career in baseball – and even spent a couple years in the majors. I remember saying to him something along the lines of, “It’s too bad Spider didn’t get a chance to play in the majors. He seems like such a nice man.” Gene looked at me, cocked his head, and said, “Son, he played all of you like a fox. You’re going to kick yourself when you go back to the office look him up.” If I could have bruised my own back side, I would have. Not only had Spider Jorgensen played professionally for 16 seasons (not including time lost to World War II) – but he spent five years in the majors. Three of those campaigns were as a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers. And the kicker: Spider and Jackie Robinson both made their major league debuts the same day, with Spider playing third base and Jackie playing first. I would have loved to have had the opportunity to tell his story. Thankfully, it’s tough to find quiet and unassuming scouts – so I’m looking forward to introducing you to some of them.

We’ve all heard the saying that a picture is worth 1,000 words.

But I’m going to test my theory that 1,000 words can be worth one picture. You’ll just have to read to the end of this story in order to see one of my favorite photographs – even though it’s been slightly doctored. I have had a copy of the original photo for 15 years. But it’s one I’ve had to keep hidden in the vault – OK, actually a closet – since the girls were old enough to recognize what a swear finger is. They’re now at the point where I can display it again, and they’ll laugh when they see the real photo. But the internet is a tricky place, even in 2016, so the edited version is what you get to see. But I think you’ll laugh at that picture, too. Fifteen years ago this week, the photograph was snapped. Fifteen years ago this week, an amazing two-game stretch took place – as Jon Lieber and Kerry Wood fired back-to-back complete-game one-hitters. The Cubs have been around since 1876, and that specific feat has only taken place one time – on May 24-May 25, 2001. I could tell you the story of those games myself, but I couldn’t do it enough justice. So I tracked down Lieber and Wood to talk about those memorable consecutive afternoons at Wrigley Field. May 24, 2001 … Cubs 3, Reds 0 … the lone hit off Lieber was a two-out 6th-inning single by Juan Castro

“That was probably the best game I ever pitched,” Lieber said. “I do remember the rain delay before the start of the game. “I seemed like my normal self, and it was just one of those games where the Reds were very aggressive – they were swinging the bat early and quickly. There was a rain delay during the game. It happened right after I pitched the 4th inning. During the delay, (pitching coach) Oscar (Acosta) comes up to me and he said, ‘How do you feel?’ And I said, ‘I feel fine. There’s nothing wrong with me. Why?’ And he said, ‘That’s what I thought, because you’ve only got 20 pitches through 4 innings.’ That just blew me away. “The game was delayed for about an hour and a half, and I think I shocked more people by going back out there for the 5th inning. I kept putting up the numbers, getting out of innings with low pitches. The next thing you know, I have this no-hitter going into the (6th) inning. There were two outs, and Juan Castro flipped a slider … I don’t think it was a terrible pitch, but it was enough for him to flip his bat out there and bloop it into rightfield. That was the story of my career. Any time I tried to finish something like that, I could never do it. Anyway, I moved on after losing the no-hitter. “For me, even though I didn’t get the no-hitter, just to be able to face the minimum number of batters for a nine-inning game is pretty impressive, in my opinion. “And then … Mr. Wood steps into the picture.” For his part, Wood remembers Lieber being in a “zone” that day and having a double-digit pitch count. “He was ridiculous,” Wood said. “But that was typical Liebs. He just went out there and, as quickly as he got the ball back, he was throwing it back to the catcher. He’d get in that zone. He had a bunch of games where he was under 90 pitches. It was pretty impressive. He took pride in that.” May 25, 2001 … Cubs 1, Brewers 0 … the lone hit off Wood was a 7th-inning leadoff single by Mark Loretta

“Me and Lieber … we were two totally different pitchers,” Wood said. “We were in a rhythm there where we were all feeding off each other. We were all throwing the ball well. “I remember Liebs was typical Liebs. He did his under two hours. He was locked in. Anytime somebody does something like that the day before you pitch, you want to do your best to follow it and emulate it. So it was a cool couple days. “My game honestly doesn’t jump out as much. I know it was Milwaukee. I couldn’t tell you how many strikeouts I had. I couldn’t tell you any particular defensive plays that were made. I do remember me and Lieber throwing back-to-back against two different teams, but honestly I don’t have a whole lot of memory of who was on that team – as sad as that is. “But I’m getting old. My memory is going,” he said with a laugh. Wood is almost 39 years old now, so he did have to ask how many pitches he threw that afternoon. The answer was 114. “That was a low pitch count for me to go nine innings,” Wood said. “Liebs had a lot of balls put in play. I tended to have more foul balls and three-ball counts. Lieber didn’t walk anybody. So he kept his pitch count down regularly.” Unlike the rainy wet conditions the day before, the sun was out that afternoon – and Lieber was in a great third-base dugout location for Wood’s gem. “Man oh man oh man, did he put on a show,” Lieber said. “I saw Kerry pitch a lot of games, but that one just stuck out in my opinion. He was untouchable. That was as close to the 20-strikeout game – he was just that dominant. He was impressive. And his command – that was probably one of his best games. He should have had a no-hitter – he was just that dominant. “For me, it was just another game. Wow, a one-hitter – OK. But then Kerry threw his game. “Kerry and I did something pretty special … That was just a great moment to be part of. I didn’t get those chances very often to be in situations like that. Kerry was just on such a different level because of the type of pitcher he was. He could do something special almost every time out. It was incredible – and pretty neat to be part of something like that.” May 26, 2001 … Wrigley Field third-base dugout … pregame … epic photo op “Me and Liebs are pretty humble guys,” Wood said. “We didn’t think much of it. We were enjoying our day off. “(Cubs team photographer) Steve Green came by before the next game. We were sitting next to each other, just kind of talking. He looked at us with his camera and said, ‘Hey you guys, put up a No. 1.’ “Me and Liebs looked at each other and we both gave Steve the finger at the same time. “That’s one of my favorite pictures. I’ve got about 1,000 pictures from Steve, but that’s my favorite one – me and Lieber. I have it hanging up in the basement.”

Do middle school math teachers get mad if their students work on language arts assignments?

I think that’s a fair question to ask. I wonder … do music teachers get upset if their little prodigies play both the piano and the drums? Man, they must get pissed. If you’re scratching your head and thinking, “Chuck, what the heck are you talking about,” then you’ll understand a dilemma I’m having. My children like to play sports. Period. They’re both good enough to compete – and oftentimes play very well – on the softball diamond, the soccer pitch and the basketball court. But there is this little problem. Sometimes, they can only be in one place at one time. Neither has been cloned. Neither participates in time travel. One place, one time. And what is the first thing a youth coach does when a kid can only be at one place at one time? A coach questions the kid’s commitment. Frankly, I’m tired of it. You want to question a kid’s work ethic if she’s goofing off or lackadaisical when she’s there … fine. You want to blame a 12-year-old in front of her teammates for a loss, instead of doing the coach thing and giving the kids credit for the victories and taking the blame for the losses … whatever. Coach, you and I will never see eye-to-eye on that. But when you question commitment because the kid is playing another sport at the same time … that raises my blood pressure. Hey coach of 12-year-olds … If my kids want to play multiple sports, shouldn’t you be in favor of that? Shouldn’t you want kids to use multiple muscles and develop multiple skillsets and thrive on being in as many competitive game situations as possible? I wrote hundreds – yes hundreds – of player biographies during my Cubs media relations days. A heavy majority of those athletes played multiple sports in high school. Some were good enough in high school to have to make a choice which sport they were going to play IN COLLEGE. For those of you who regularly take a look at my posts, I’ve recently written about Brian McRae – who was good enough as a high school athlete to get selected in the first round of the baseball draft and get Division I scholarship offers in football. I recently wrote about Kevin Tapani – who pitched in the majors despite not having a high school baseball team to play on. He played other sports – and that got him noticed. I talked to Kerry Wood this week – he did pretty good for himself, didn’t he – and he talked about the joy of watching his children play a bunch of different sports. And it’s not confined to former Cubs. I talked to one of the new Chicago Bandits softball players earlier this week – Morgan Foley – about the fact that she went the Division II route for college because she couldn’t decide which sport to devote her attention to until the spring of her senior year in high school. As she said, “I really fell in love with softball and basketball – and I kept playing them all through high school … For me, I couldn’t pick one. I loved them both. I didn’t want to pick one. I don’t think kids should pick, because you need to be versatile. If you’re an athlete, you should be able to play multiple sports. Whatever sport I was playing, that was my favorite sport.” Four years later, Foley is a professional athlete. Coach … kids can totally be committed to many things. Be thankful that they’re committed to not getting into trouble. Be thankful that they’re committed to getting along with teammates. Be thankful they want to play sports – and that other coaches and/or parents didn’t already burn them out. But don’t question commitment if a kid plays multiple sports and chooses the other sport from time-to-time. Maybe there’s a specific reason they picked the other sport on a specific day. Maybe that reason is you.

Imagine if this scenario took place in a major league baseball game:

The Cubs are trailing 8-7 … bottom of the 9th inning … two out, but the tying run is on third base. The opposing team is doing everything it can do to “accidentally” slow the game down. And then the umpire yells “Time” – not for timeout, but because the game clock has run out. And the game ends there. How bad a taste would that leave in your mouth? Now, imagine the same scenario – but there was one more pitch in the game. It’s a wild pitch … the ball goes to the backstop … the tying run scampers home. And now the umpire yells “Time” – again, because the game clock has run out. The score is tied 8-8, but the Cubs were trailing 8-7 when the inning started. Because they were trailing entering the inning, the score reverts back. So they lose by a run. Now, how bad a taste would that leave in your mouth? Well, I witnessed the first scenario take place on Sunday – and scenario No. 2 was literally one pitch away. And I don’t get it. This passage was in the rules for a softball tournament my kids played in this weekend: Elimination Play - No new inning will start after 1 hour and 10 minutes. Drop dead at 1 hour 20 minutes, if inning is not complete, score reverts to last full inning, if home team is winning, inning doesn’t need to be completed. If the game is still tied after the inning has been completed, International Tie Breaker rules will apply until the outcome of the game is determined. B) If an umpire determines that a team is intentionally delaying the game or there is an injury, time may be added to the clock. The amount of time added will be up to the discretion of the umpire. Before I go on, please know that I’m not blaming the tournament my kids played in – as this cut-and-paste is probably used in thousands of tournaments each year. But I do blame the person or persons who initially wrote this rule without thinking of the consequences. And honestly, I don’t blame the coaching staff from the other team. I can’t tell them they’re wrong when they played by the rules of the tournament. And I won’t blame the umpire. It’s hard to determine what’s intentional and what’s not. I can think intentional – but I can’t prove it. I’ll say this, which may come as a shock to many parents of 12-year-old athletes – but you’re 12 year olds are NOT professional athletes. Someday … maybe. But in 2016 – they’re not. And my kids are 12 years old. They play travel softball and travel soccer and travel basketball – and have for years. We’re not a family of newbies when it comes to travel sports. But soccer and basketball are timed sports. When you have a lead, part of strategy dictates you do everything you can to keep the clock moving. Softball (and baseball) are sports where no lead should be considered safe; that’s the essence of what makes them special. So my question is … Who created a rule that actually encourages coaches to delay a game as an “accident” in order to win? In essence, who created a rule that actually encourages coaches to cheat? Look, I’m not writing this because my girls’ team lost a game. You learn much more from losing than you ever do from winning. And no, I’m not saying that because of all the time I spent with a certain major league team – so get that thought out of your head. The softball team had trailed 8-0 – and clawed back to make it a one-run game. The teamwork and resiliency and cheering each other on will pay dividends down the road as they go from tournament to tournament. Losing a tough game creates plenty of teachable moments: We need to work on this … we need to improve on that … we need to tighten up the defense. So on Elimination Sunday in a tournament, why is a “drop dead” time of game the big determinant? Why are kids taught by their coaches and parents to untie their shoes so they have to go to the plate and call “time” and re-tie them – a great 30-60 second stalling tactic? Why are new catchers brought into a game when the game is “on the clock,” so that you have to wait until they get their equipment on and effectively slowing down the game? Why are coaches holding their players back for an extra 30-second team huddle before sending them out – when they weren’t doing that earlier in the game? In soccer, I get it. Timed game. One goal lead, kick the ball as far as possible out of bounds and hope a parent from the other team doesn’t run it down. It’s a timed game. In basketball, I get it. Play “keep away” with the ball and hope the refs don’t call every foul and keep the game moving. But in softball and baseball tournaments, why change the rules? What does proving you can stall better demonstrate to anyone?

Photo courtesy tradingcarddb.com

It’s been pretty cool reconnecting with some of the unique personalities I worked with during my quarter century with the Cubs – as I’m on a mission to track down players I worked with to talk about their playing days and find out what they’re up to now.

I recently caught up with Les Lancaster, who pitched for the Cubs from 1987-1991 – and is now a pitching coach in China. Since the time I spoke with him, he has been promoted to his organization's major league coaching staff. ***** Chuck: The Chinese Professional Baseball League websites are not easy for me to navigate. Tell me a little about what you’re doing. Les: “I’m here in the minor leagues with the Elephant Brothers club leagues – and we have three American coaches. I use interpreters. They’re young kids, and they’re not bad. We have two of them. One of them stays with the hitting coach and one of them stays with me..” Chuck: Who are the other coaches who are there with you? Les: “The manager is Dallas Williams and the hitting coach is Razor Shines.” Chuck: I know those names. Razor Shines was in Indianapolis for a long time, right? Les: “Absolutely, that’s him. He was with the Expos when he played and he coached in the big leagues with the White Sox and the Mets.” Chuck: Do you have American players? Les: “We have one. We’re only allowed three imports in the big leagues. And they have three pitchers right now. They’re probably getting ready to move him up and send somebody out.” Chuck: I know you pitched in Taiwan during your professional career. How did you wind up back over there? Les: “An agent got a hold of me out of the blue. I guess he contacted somebody who was a manager in Indy Ball (independent ball) that I knew. He connected me with the manager here in the minor leagues.” Chuck: After your big league career, you got to see the world as a pitcher. Les: “I played in Italy. I played in Mexico. I played in Croatia. I loved Italy; it was awesome. Baseball there at that time wasn’t that great; they still used aluminum bats, and you were only allowed two imports.” Chuck: How was the language barrier over there? Les: “Italian and Spanish are similar, so I was able to pick up words a lot easier. But you know what, a lot of places here – especially the younger generation – they understand English somewhat.” Chuck: When you have mound conferences, is your interpreter allowed to go out there with you? Les: “He’s allowed to go out there with me to talk, so it’s not a problem. But the umpires are real quick about coming out there because the games are so slow.” Chuck: Was that the case when you were over there in 1996? Les: “I think it’s a generational thing. It’s slower now. Overall, the talent is a lot better – especially at the major league level position player-wise.” Chuck: How are the pitchers? Les: “To me, they’re underdeveloped. They’re afraid to throw a fastball. They throw a lot of off-speed any time in the count. It doesn’t matter what the situation is. They don’t pitch to the situation. With my team, I’m trying to get them to pitch a little bit more Western. Until they have success and trust it, they don’t believe it – because they’re so accustomed to that old way. They’ve adapted pretty well to me and what I’m trying to do. It hasn’t been too bad. They’re not used to having fun. It’s really like an army. They’re just so used to hearing negativity when they’ve done badly. They’re not used to us just talking to them like a human being when they mess up. Talking to them helps a lot.” Chuck: What kind of schedule do you keep over there? Les: “You wouldn’t believe all the days off we have. It gets boring over here at times. We only played three games this week. We played Tuesday, Friday and Sunday. That was it. Every other day was an off-day. If we have two days off in a row, we’ll practice one of the days.” Chuck: How long will you be there? Les: “At least through September, for sure. I got here January 15 – that’s when spring training starts. The big league team’s season began March 19. They play all the way through the end of September, too. It’s a long season for them.” Chuck: With all those off-days, do you even need a five-man rotation? Les: “I say that all the time. There’s no sense in it. They have Mondays off for sure every week, and at least one other day off. I don’t know why they go to a five-man rotation. We only use three starters. That’s enough.” Chuck: How do you keep busy? Les: “I’ll usually go around and see the country. The off-days give me the opportunity to do that. My wife just left yesterday, and we had gone around seeing different parts of Taiwan. That was pretty neat. It’s beautiful country around here. I’m down south of Taiwan – and they consider it the country. So when you go up to the bigger cities, there’s definitely a lot more stuff. I do enjoy it over here. It’s fun.” Chuck: You’ve had a pretty interesting path in your post career. You’ve been in a lot of leagues and been in a lot of places. Les: “Yeah, I definitely have. I can probably say that I’ve done just about everything in baseball. From being part owner to being like a GM to doing player contracts. Field maintenance. Hanging billboard signs. You name it, I’ve done it.” Chuck: What stands out to you? This is what I wish I could have done all the time. Les: “I liked managing a lot. I really enjoyed it. And dealing with the players’ contracts like a GM – that was fun. Being a manager in independent ball and building your own team was very exciting.” Chuck: Long term, what do you want to do? Or can you even say that at this point? Les: “I’m not real sure. I’ll just continue in baseball year-to-year. I just enjoy it.” Chuck: Looking back at your Cubs career, what was most enjoyable for you? Les: “Definitely my rookie season of 1987. To be able to come up with the older guys – Rick Sutcliffe, Ryne Sandberg, Jody Davis, Keith Moreland, Andre Dawson. That was awesome – to step in with people of their magnitude right away. And, of course, me and Greg Maddux being together all those years made it fun.” Chuck: Your story back then was pretty good – an undrafted free agent in 1985 getting to the majors two years later. Les: “Yeah, I happened to get with an organization that needed pitching. I opened eyes quick and they pushed me through quick. I appreciate that. Also, of course, the 1989 season – what a great year it was for us all.” Chuck: The Cubs might not have gotten to the playoffs without the role you played all year. Les: “I appreciate that. It was a great season. I can tell you that.” Chuck: You probably have some great memories of just hanging out in the bullpen with Mitch Williams. Les: “No doubt about it. Mitch was definitely a character. He still is. He’s not going to change. I was able to play with a lot of great players, and that was something special.”

I was talking to a former Cubs colleague the other night, and the name Mickey Morandini came into the conversation.

Remember Mickey? Too thin, too much hair – and a fundamentally solid second baseman who had a decent big league career. Morandini played a pivotal role for the 1998 Wildcard Cubs, and he did a marvelous job filling the gap left by the retirement of Ryne Sandberg after the 1997 season. One of these days, he’d be a good guy to connect with to talk to about his Cubs days. So would the guy the Cubs traded to acquire him – Doug Glanville. I’ll get right on both of those names. Hearing Mickey’s name was more than a “Whatever Happened To” thought, though – especially since he’s not that hard to track down (he’s now the Phillies’ first base coach). Hearing his name was a huge reminder of the day the Cubs acquired him. December 23, 1997. The day my pager buzzed. No, this isn’t comparable to “Where were you when President Reagan was shot?” or “Where were you during 9/11?” From a technology standpoint, it’s the answer to the question of “Where were you the one and only time your pager went off? Right around the time of the baseball strike in 1994, my media relations chief – Sharon Pannozzo – had me start carrying a pager. This way, should something happen when I wasn’t around the office, I could obviously get paged. Either nothing happened, or I was around the office way too much – but the pager never buzzed. Ever. Well, that’s not exactly true. I called myself from time-to-time to see if it actually worked. The battery inside lived a good long quiet life. By 1997, even I had a fully loaded flip phone – meaning I had to manually lift the antenna when placing and receiving calls. But the Cubs never asked for the pager back, so I carried it in my pocket religiously just in case something happened. I even got to test the battery dialing the pager from the flip phone – and it buzzed every time. And on that fateful December 23, the little pager hummed. I was driving Michelle – who was still nearly three years away from losing a bet and having to marry me – to a rendezvous destination point with her mom. Three months earlier, Michelle had shattered her ankle playing flag football while I was on a road trip. Even then, the pager didn’t go off; I found out via a post-night game phone call after returning to our team hotel in Houston. So Michelle, her external fixator and her crutches were in the back seat as I drove to the Dwight/Morris exit off Interstate 55 in central Illinois – about a 90-mile ride. And just as I was pulling off the highway, this loud buzzing sound occurred. The first thought was, “What the heck is that?” The second thought was, “Really, what the heck is that?” The third thought was, “Why am I getting a 911 message from the media relations office? I know they have my cell number.” The fourth thought was, “Stop thinking. Call the office.” I flipped open my phone, pulled up the antenna and dialed Wanda Taylor, the third member of our three-team staff. She apparently was the lowest in seniority, meaning she got to work on December 23. After thanking her for paging me – “Yay, it worked” – I asked what was going on, and inquired why she paged. Wanda told me the Cubs had made the Glanville-for-Morandini trade … that neither player had been told … that the trade was going to be announced in a couple hours … that she couldn’t find Sharon … and she tried me on my phone – but that I was outside the network area when she was calling. The never-before-utilized pager turned out to be the knight in shining armor – or in this case, the knight in shining plastic. At that specific point in time – in a parking lot in front of an Arby’s or Burger King or whatever was in existence on that day right off the interstate – my phone was working. Wanda could hear me now. Being the hero that I am, I slowed the SUV long enough for Michelle to hobble out, tossed the crutches at her, waved to her mom, and got back on I-55 – racing to the ballpark. These were the good old days, meaning I couldn’t call Wanda back for another 30 miles or so until I was back in an area again. I asked her to Xerox multiple items and track down information, and I was in the office a short time later – writing the press release. I’m going to have to talk to Morandini and Glanville one of these days about getting traded the day before Christmas Eve. I wonder if they found out by phone call or pager. Editor’s Note: No crutches were harmed after being tossed from the vehicle. They still hang out in the author’s garage.

It’s been pretty cool reconnecting with some of the unique personalities I worked with during my quarter century with the Cubs – as I’m on a mission to track down players I worked with to talk about their playing days and find out what they’re up to now.

I recently caught up with Brooks Kieschnick – an outfielder for the Cubs in 1996-1997, and later a relief pitcher for the Brewers in 2003-2004. ***** Chuck: I’m going to start by saying I want to learn more about what you’re doing now. It sounds like everything you do is in the medical field. Brooks: “I work for a medical distributorship and I sell spine implants. I’ve been doing that since I retired. I really enjoy it. I get to go into the (operating room) and I’ve seen a ton of surgeries. It’s been a really neat opportunity for me for life after baseball. I’ve been with them for a while now. I also own Alamo Ice House (in San Antonio), and we serve barbecue, beer and wine. And we have live music as well.” Chuck: I hope after going to your restaurant/bar that people don’t need work on their spine. The two aren’t connected, right?! Brooks: “Exactly. No, they do not coincide.” Chuck: You said you get to go into the OR. You really get to watch? Brooks: “I do. Absolutely.” Chuck: How did you get into the field? Brooks: “Toward the tail end of my career, one of my family friends said she’d think I’d be great at this. I started talking to them and went through the interview process, and they said the same thing and basically offered me the job. The more I started thinking about it, ‘Whenever I retire, I’m in.’ I started the process of learning everything about the spine and about all the equipment and all of the stuff like that. It was a smooth transition – but also one that was very hard to make.” Chuck: The information you’ve learned being in this field – could any of it have applied to you during your playing career, or are they two totally separate entities? Brooks: “As far as what I’ve learned about the spine – no, not really. But one thing that does coincide is selling yourself. There are tons of products out there, and a lot of those products are the same. All of the products are FDA approved, so they all work. Put them in the right person’s hands … as a salesperson, you’re selling yourself. That’s what I did during my playing career. You’re not only playing for the team you’re on, especially during spring training … you’re playing to be seen by all 30 teams as well.” Chuck: That’s an interesting way to look at it. If there’s one message that you want people to know about the products you sell, what would that be? Brooks: “My products relieve back pain, leg pain, neck pain, arm pain. All the pain that you have is due to your spine. We will fuse your back and restore height. Also, any kind of bulging disc or any kind of stenosis – which is the narrowing of the canal – we’re able to relieve that. Don’t wait too long to where you start losing function – especially if you have neck pain – losing function and muscle. Get it done. The surgery itself will be painful, but the long-term effect will be great for you.” Chuck: That was definitely an interesting career switch. Now I’ll switch over to your playing days. What memories do you have of playing in Chicago? Brooks: “It was amazing. Wrigley Field, there’s nothing to really compare it to. It’s the field of all fields. Without being too cliché, it was a ‘Field of Dreams’ to be able to play at Wrigley Field. One thing I can say about it – it was too short. I would have loved to have played there for a long time. But such is life. My time at Wrigley Field was just incredible. The history and the mystique of playing there was awesome.” Chuck: You came in as outfielder with the Cubs – and ended your career as a relief pitcher and jack-of-all-trades with the Brewers. How do you characterize your career? It might not have been real long, but it was unique. Brooks: “You know, it was long – but it wasn’t long in the big leagues. I played 13 years. I considered myself a baseball player. Maybe I wasn’t a pitcher. Maybe I wasn’t an outfielder. I was a ball player. I just wanted to play. I didn’t care where you put me – first base, outfield, third base, pitch, catch. I didn’t care. I just wanted to play and to do anything to help the team win. I guess somehow along that line the first few years in Chicago I got labeled as an insurance policy – a guy you can put in Triple-A and call up if somebody gets hurt and be serviceable. For some reason I got labeled that early in my career. Given the time that I played full years in the minor leagues, getting 400 to 500 at-bats, I always put up numbers. That was one thing I wanted to get a chance to do in the big leagues. After you get labeled, then you just continue to try to reinvent yourself. After leaving Chicago, I did that. The worst thing was getting hurt in ’98 and basically missing the whole year. Coming back in ’99, I put up great numbers in Edmonton. In 2000, I put up big numbers in Louisville and ended up getting a cup of coffee with the Reds. Then putting up good numbers in Colorado and spending half a season in the big leagues with them. After that, when it wasn’t happening for me as far as getting a job where I’d have a chance to make a big league club, I decided ‘You know what, I’m getting tired of being the insurance policy. I’m tired of being that guy. I pitched in college – I want to give pitching a shot. If it doesn’t work out, then I’ll leave with no regrets.’ ” Chuck: You did something that pretty much no one has done. You worked your way back and put yourself in a position where you’d come to the ballpark every day knowing you would play – but you didn’t know what position that would be. Not to throw stats at you, but in 2003, you became the first player in major league history to hit home runs as a pitcher, designated hitter and pinch hitter in the same season. Brooks: “I had so much fun in Milwaukee. I really enjoyed the game again. Yes, it was still a business. But it was a lot more fun for me. I felt like I was back in college. I got to pitch. I got to DH in interleague games. I got to pinch hit. I played the outfield a couple times. Man, it was awesome. This is what baseball is to me. It was fun, and I was having a good time doing it that way. And not grinding. And not trying to get two hits in one at-bat, if you know what I mean. It was a deal where I knew I had value with them and they valued me and really enjoyed what I brought to the table. I was lucky enough to play for an awesome manager in Ned Yost – who you wanted to play hard for. He loved his players. He loved the effort. And Milwaukee was a really blue-collar town that was awesome. They loved to see the guys that maybe weren’t the superstars who were out there battling every day. And I was never a superstar and never claimed to be. You played the game, you played it hard and you played it the right way.” Chuck: If you could have done it again, is that the way you would have wanted your entire career to be – knowing you’d be playing every day, but in a different role? Brooks: “There are a lot of clubs that wouldn’t allow you to do that. I was very lucky to have Doug Melvin be that GM to tell me, ‘You know what, what you did last year in Triple-A with the White Sox is what we want you to do here in the big leagues with Milwaukee.’ And I was like, ‘Absolutely. I’ll do whatever you want me to do.’ And Doug Melvin put his neck out. Being a small-market team like that, he took a chance on me – and it worked out for a couple years. It allowed him to keep an extra pitcher or an extra position player because I was able to do multiple things. It allowed him to keep people he might not normally keep because I could fill in certain areas or certain positions for him.” Chuck: What was your biggest baseball moment? Was it in the majors, or was it as a pitcher/hitter at the University of Texas? Brooks: “It’s funny, when you say biggest baseball moments, one that comes to mind was in high school – hitting a walk-off home run on live TV news. It was an extra-inning game, and it was the first time I played a baseball game on live TV. I think one of my greatest moments, too, was having Coach Gus (Cliff Gustafson, Texas’ baseball coach for 29 years) my junior year – we’d won the regionals, and we were about to go to Omaha for the College World Series – and he called me out onto the field to address the fans. He said in his 20-plus years of coaching he had never called a player out there before to address the fans – and that was really a humbling, phenomenal moment in my career. Professionally, you’ll always remember your first hit. You’ll always remember your first home run. I was lucky enough to do that and also get my first win on the mound. To me, every day in the big leagues was a memorable moment. Every day you got to walk to the ballpark and put on a uniform and play in the big leagues – those were the best moments. There’s not one I can just pick out and say, ‘Oh my gosh, that defines my career.’ My career was defined by being able to go to the ballpark in the big leagues and throw on a uniform.” Chuck: Do you go back to Austin to see games there? Do you ever notice No. 23? Brooks: “Oh yeah. It got retired about seven years ago. It’s pretty neat to know that nobody will ever wear my number there again. It’s enshrined – and it got rewarded for leaving a lot of blood, sweat and tears out on that field. It was awesome and humbling for me – to go to such a big university and get recognized by that.” Chuck: This has been terrific. I’m looking forward to sharing all of this. Brooks: “So you get to tell your stories. But do you remember any stories about me. What do you remember about me during my short little two-year stint there? What’s your take on that?” Chuck: You’re either going to love this story or hate this story. Brooks: “Either way, it’s a story.” Chuck: The one that jumps out is when Al Goldis, who drafted you for the Cubs, was describing you to me before the 1993 draft. All he kept talking about and demonstrating was how you swiveled your hips at the plate – and that the women were going to love watching you bat just to watch your hips. Brooks: “Yeah, that was it. In college, we’d go to our rival – Texas A&M – and they’d wave dollar bills at me. They’d call me Elvis and all that kind of stuff. It was funny.” Chuck: Like I said, I wasn’t sure how you’d take that. Brooks: “Al is a great guy. I love that he took a chance on me and loved what I brought to the table. It was a really different time then in Chicago. From 1993-1997, we went through two or three GMs and three or four managers. It was always ever-changing. If they had stayed with the same regime, different things might have happened. You just never know.”

My mom is a source of amusement to me.

There. I’ve said it. I don’t know why. I do hope lightning doesn’t strike me for saying it – because I’ve already recently written about how her mother is steering my new career from some strata way above where I’m sitting. And if you don’t believe that, who do you think just dumped the word “strata” into my brain? So in honor of my mom on this most holy of holidays, I’m using this little space to talk about her. Let’s face it, any son can get his mom a jewelry link. Thanks to www.chuckblogerstrom.com, I can give mine a story link. It’s the gift that keeps on giving. And I find my mom humorous. If I was hired to write the Marlene Wasserstrom story, it would start out like this: "A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away … my mother was born.” She’ll roll her eyes at me, but she’s heard me say it. I like to remind my kids that when Grandma Marlene was their age, she lived on the prairie and traveled by stagecoach. That’s not exactly true. When she was their age, she was shuttled around in a Model T. What can I say? My mom is easy prey. My mom is the one who shows up at the kids’ sporting events with a book and a Diet Coke and a 74-pound purse full of Werther’s. What’s not funny about that? I know she finds it amusing when she talks about what I’ll do when it’s time to put her in a home – and I straight-face tell her that I’m putting her on a one-way bus to my brother’s house in St. Louis. Look, you might think that’s mean, but she knows I say it with love. And my mom and I both know my sister-in-law takes in borders all the time. What’s one more house guest? My mom is the one who went to school with a grandparent of someone on every travel team my girls have played on. Guaranteed. She’s the one who you don’t want to go shopping with because you know she’ll bump into someone she knows in every aisle. By the way, that gene skips a generation. My two little ones now have a hard time going into a restaurant without seeing someone they know. And I find all of that humorous. It got to the point that we used to play a game called “Six Degrees of Marlene.” It was based on “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon.” Then we did the Mom-to-Bacon math … (1) Mom has a first cousin named Michael. (2) Michael was the executive producer of the TV show Quincy, which starred Jack Klugman. (3) Mr. Klugman was in the movie Days of Wine and Roses with Jack Lemmon. (4) Mr. Lemmon was in JFK with – you guessed it – Kevin Bacon. We couldn’t even get to six degrees. Too easy. Over this last little stretch, I’ve done a lot of housekeeping looking for scrapbook items. My mom has been a math teacher longer than I’ve been on this earth, so I even found an old Haiku I wrote about my mom: My mom teaches math. She adds, subtracts, multiplies. I hate calculus. See, I give my mom credit for my sense of humor. I wrote that one in college, by the way. In honor of Mother’s Day, I’m trying my hand at a new math Haiku. Trigonometry. Is that length times width times height? Nope. Geometry. Doesn’t that put a smile on your face? It’s easy to find humor in someone who is always there for you … and is always part of your life … and is always concerned about your own kids … and is always worried about you in good times and bad. My mom might not find me funny all the time, but if I gave her a sappy Mother’s Day card today, I’m sure there would be a point in the day where she’d say to herself out loud, “Henry, that card was nice. What’s wrong with Chuck?” I just thought of something … if it wasn’t for my mother, I wouldn’t be here right now. Think about that. So mom, thank you for my wit. And if you only think some of it is funny, thanks for making me a half-wit. Happy Mother’s Day!

I often get asked if I miss working in baseball.

The honest answer is “sometimes yes, most of the time no.” I miss it a little more now that I’m writing stories about the game – but I enjoy this little writing career way more than the baseball grind. But I do admit to missing “the rush.” I don’t often pat myself on the back or give myself credit, but if I was allowed to give a 10-second elevator pitch about my time in the Cubs’ Media Relations department, I would tell you with the utmost of confidence that I was good at proactively being ready when game “events” occurred. For example, if a Cub hit a grand slam, I had the information ready for a press box announcement before the ball landed. Or if a player hit a 16th-inning home run, I was out of my seat and announcing to tell everyone within earshot that it was the latest homer in Cubs history – while the ball was still in flight. There was nothing like the adrenaline rush of scrambling from TV booths to radio booths to telling the Cubs beat writers to press box microphones to let everyone know about a “first time it happened” moment or a “last time it happened” occurrence. The Cubs had been around 110 years before I got there; whenever something unusual happened, we weren’t exactly talking small sample size. One of the greatest “rush” days I’ll ever experience took place 18 years ago today – May 6, 1998 – as this is the anniversary of Kerry Wood’a 20-strikeout game. If only I wore a mental Fitbit, my brain probably walked 100,000 steps that Wednesday afternoon. Woody’s pitching performance was the most dominating I’ll ever see. Period. Think about it … He was a 20-year-old kid in just his fifth major league start – and he struck out 20 of the 29 batters he faced. Hard to believe, but just two starts back, he didn’t make it through the second inning in Los Angeles – and you couldn’t help but wonder if he was ready for all of this. And on this day against the Houston Astros, he was a boy among men. This wasn’t a September Triple-A roster – and even if it had been, that wouldn’t negate the fact that he struck out 20 of 29. The Astros’ lineup that day featured Craig Biggio and Jeff Bagwell – and also included Moises Alou, Derek Bell and Ricky Gutierrez. I certainly can’t say that I knew May 6 would be a record-setting day, but when Woody struck out the side in the top of the 1st inning and Houston’s Shane Reynolds followed with strikeout-strikeout-strikeout in the bottom half of the frame, you knew this might not be a typical ballgame. After striking out the side in the 4th inning, Kerry had eight strikeouts. I could do the math; he was on an 18-strikeout pace. Most of the time, when you do math like that, the pitcher’s final pitching line only goes up by one or two. But Woody tossed that theory through the window by fanning all three batters in the 5th. At that point, my daily scribble sheet was starting to see some pretty good scribblings. I was slowly filling in the information I had access to via my own Cubs records collection and two major league record books I had in my press box cabinet. One-by-one, the numbers were written on paper … 12 … 13 … 14 … and up to 19. I had No. 20 staring me in the face in the Official Major League Baseball Record Book. 6th inning … one strikeout … now at 12. 7th inning … strikeout, strikeout, strikeout … 13, 14, 15. The last one tied Cubs nine-inning and rookie marks. Whole sentences, written out neat enough for my boss – Sharon Pannozzo – to read on the in-house public address system. 8th inning … strikeout, strikeout, strikeout … 16, 17, 18. By now, I was in constant contact with the famed Elias Sports Bureau – where they were just as much one step ahead in anticipation of Woody’s next strikeout. No. 16 set the Cubs’ nine-inning record. No. 17 tied the major league rookie record and the Cubs’ overall record – done in a 15-inning outing. No. 18 established records for both. Partial sentences, in hieroglyphic scribble, just legible enough for Sharon to hand me the mic and tell me to read it. And then came the 9th inning … Pinch-hitter Bill Spiers went down swinging for a seventh straight Kerry Wood strikeout – equalling another Cubs record. But who cared about that? It was strikeout No. 19 – tying a National League record accomplished only four previous times in 122 seasons. Future Hall of Famer Craig Biggio was then cursed at after putting the ball in play and grounding out for the second out of the inning. And up to the plate came Derek Bell, and all I could do was try not to hyperventilate. Woody quickly got to two strikes, and his curveball was dancing. Bell had no chance, going down swinging for strikeout No. 20 – tying a mark only reached before by Boston’s Roger Clemens. I vividly recall running down to the field after the game to assist with the live postgame interviews – and Woody was visibly trembling. I had no idea if he had truly processed what had happened. But more than anything, I’ll never forget the in-game rush of researching and tracking down and providing information as his strikeout total grew and grew. On days like today, I do miss that rush. It has been an interesting last week for me. This morning, I completed my third Skype interview in five days – with two Chicago Bandits professional softball players currently playing in Japan (buy the Program/Yearbook during the Bandits’ season!) and former Cub Les Lancaster, who is coaching in Taiwan (story coming soon to this site). I conducted an iPhone Facetime interview with a gentleman in Mumbai on behalf of one of my clients. I did a chat interview with a Libyan-born poet … who is now a professor at Michigan … who had gone to Cairo on a one-year sabbatical … who is now on vacation in Spain … via Facebook Messenger … while riding on a rush-hour Metra. I started a conversation which led to an interview – after direct messaging that person through Twitter. And, to top it off, I was a guest for a MLB Trade Rumors Podcast. I can’t explain it; there have been over 2,500 downloads of the show. Chuck Wasserstrom – now curing people of sleep apnea … one-by-one. This sure is a far cry from when I started with the Cubs. Hard to believe, but the entire Media Relations office in 1986 – four full-time people plus an intern – had two computers to use. One was a desktop for general office use. The other weighed about 20 pounds and traveled with the team. Those were the pre-Internet/pre-smartphone days. To try and put into perspective what baseball media relations life was like back then, please consider that the Cubs didn’t purchase their first multi-purpose copier until after the 1986 season. Until then, if you needed something produced in bulk, you needed to use the Gestetner. That’s right, before Xerox, there was the Gestetner. If you don’t know what a Gestetner was, I’m keeping my fingers crossed that you don’t actually go and look it up. I’m afraid of what you’d find. Very … afraid. Basically, it was a very messy mimeograph-like machine that was the size of a VW Beetle. It was designed to reproduce one page at a time … not very quickly … and had no interest in making your life easier. It was loud. It was cantankerous. I was only an intern in 1986, so I didn’t know any better other than to do what I was told. On mornings of game days, my job was to get the game notes pages (sometimes page by page) and statistics pages from the media relations office – located upstairs basically at the corner of Clark and Addison streets behind the Wrigley Field marquee – to the bowels of Wrigley Field. “Bowels” is the polite word. All of the action took place in the far leftfield corner … underneath the old marketing department – where you walked through actual offices occupied by marketing higher-ups to get to a flight of stairs going down … then passed by the legendary Jay Blunk and desks sometimes occupied by Billy Williams or Jimmy Piersall … to reach a fenced-in back portion of the sub-basement. And once you reached that place we called Hell, you found the Gestetner. I actually had it easy. A full-time media relations staffer, Ernie Roth, had to deal with this thing every single friggin’ day. One year before, he had been finishing up school and playing baseball at Amherst. Now, he was wearing a neck-to-shoes body-length apron and trying to get blank ink out from under his nails on a daily basis. I learned right away that baseball wasn’t glorious. No job was too small – although if Ernie had called in sick and I was told to take over Gestetner duty, we might have tested that theory. Game notes had to be produced every day. Stats packets had to be produced every day. Ernie would churn out “x” amount of Page 1 of the notes … then Page 2 of the notes … and so on and so on. Then, while he cleaned his fingertips – since he couldn’t touch anything without leaving black marks – those of us in that sub-basement backroom with him would be collating, manually stapling and distributing the information packets. And it’s not like we had a lot of time to get all of this done – as Wrigley Field was still a lights-free environment back in 1986. It wasn’t all manual labor and black ink, though. This was where you learned about teamwork. This was where you learned how to deal with stress; the game was going to start whether the broadcasters had their notes and stats – and no one wanted to anger the broadcasters. This was where you learned to navigate an elevator-free Wrigley Field 45 minutes before first pitch when the beer lines were long. Today, I can write from any Starbucks. I can communicate anywhere in the world. I can brag about being on a Podcast. But I wonder if those stories will stand the test the time. I know thoughts of the Gestetner still make me shiver. |

Details

About MeHi, my name is Chuck Wasserstrom. Welcome to my personal little space. Archives

August 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed